Inside rapid response and negotiations in ransomware incidents

When a cyber incident begins, minutes can determine whether a business contains an intrusion or suffers large-scale data theft and operational disruption. That initial interval, described by specialists as “stopping the bleeding”, is the focus of dedicated first-responder teams that aim to limit attackers’ access and prevent a partial breach from becoming a full-blown ransomware event.

S-RM, a cybersecurity firm based on Whitechapel High Street in east London, has developed a prominent, largely word-of-mouth practice in incident response and ransomware negotiation. The company says it operates the UK’s largest cyber-incident response team, with a first-responder service of about 150 experts worldwide.

S-RM’s clients include organisations that retain the company as a precaution, victims referred by insurers and businesses that call in panic after discovering an attack. The firm’s rapid contact metrics are a selling point: “On average we’re getting back to clients within six minutes,” says Ted Cowell, director of S-RM’s cyber business arm. He describes that window as critical because attackers often need time after their initial penetration to identify valuable targets.

Cowell, a Cambridge-educated Russian speaker, says a quick response during this reconnaissance phase can lead to markedly different outcomes. Attackers typically take time to map networks, determine what systems and data are most valuable, and plan exfiltration or encryption activity. Restricting their access early can prevent the detonation of malware across systems and limit the most operationally damaging effects.

Incidents vary in scale. S-RM recounts cases in which a short call with a client ballooned into a coordinated 24-hour effort involving rotating specialists. In one example involving the ransomware group known as Scattered Spider and a retail victim, what began as a brief Teams call became an around-the-clock operation to stop malware deployment and restore systems.

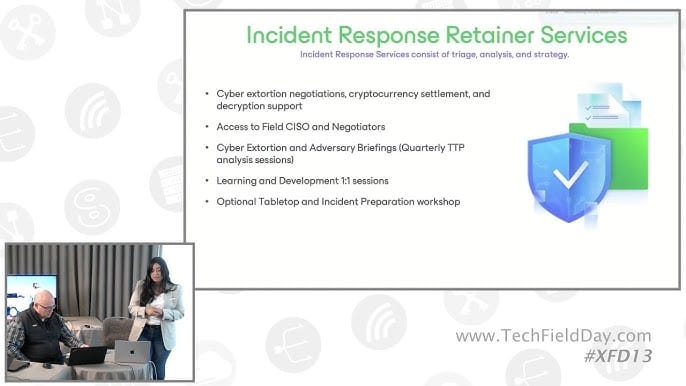

Services described by S-RM include forensic analysis, containment and restoration. As the sector has evolved, restoration and recovery have grown in importance. Companies increasingly prioritise getting systems back online as quickly as possible, with detailed forensic review sometimes treated as a secondary step.

Alongside technical containment, S-RM and similar firms provide “extortion support” — advising clients through decisions on whether to pay a ransom, and in some cases participating in negotiations. That role has drawn ethical scrutiny because payments can enrich organised criminal groups.

Cowell says the firm is often instructed by the policyholder or the insured and that its stated ambition is to guide decisions toward non-payment “wherever and whenever possible”. He frames the role as providing structure and experience in situations that clients will likely not have encountered before. “Our role is to facilitate strategic thinking,” he says.

Part of that advisory work is educating boards on the nature of ransomware groups. “Why should we pay these criminals?” is a question S-RM says it asks clients. Cowell describes ransomware actors as organised criminal enterprises with reputations to maintain; more established groups, he says, are likelier to honour settlements by deleting stolen data or providing decryption keys.

That track record gives some organisations a degree of predictability when considering payment. S-RM compiles intelligence on negotiating patterns, group behaviours and reliability, and it raises considerations around sanctions and the potential for funds to reach state-linked actors. Cowell cautions that sanctioning state-linked groups is often ineffective: listed actors tend to disband and re-emerge under new names, a dynamic he likens to a game of “whack-a-mole”.

Despite the moral objections to funding criminal enterprises, businesses sometimes decide that payment is the most rational option for their circumstances. Cowell emphasises that the decision rests with the company involved; response firms offer a framework and options rather than dictating outcomes.

The changing risk calculus has fed demand for services beyond negotiation. As corporate reluctance to pay ransoms grows, investment in restoration, resilience and incident preparedness has increased. Organisations are seeking to harden systems, limit the window available to intruders and improve crisis decision-making processes.

National cyber authorities have also shifted their posture in recent years. Cowell says the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre has transformed and now plays a more proactive role, reaching out to potential targets on the basis of intelligence and facilitating information sharing. The agency has moved from primarily gathering information to convening actors and supporting victims, he says.

That collaborative model aims to reduce the impact of incidents through rapid intelligence exchange and coordinated responses. It also reflects a broader industry trend: combining technical containment, negotiated settlements where chosen, and restoration work into a single, fast-moving response to limit damage and restore operations.

As ransomware groups refine their tactics and the commercial response market expands, incident response teams like S-RM continue to position speed, expertise and strategic guidance as essential to preventing intrusions from becoming existential crises for affected organisations.

Key Topics

Cyber Incident Response, First Responder Teams, Rapid Response Time, Containment And Restoration, Forensic Analysis, Extortion Support, Ransomware Negotiation, Ransomware Payment Decisions, Ransomware Groups, Scattered Spider, National Cyber Security Centre, Incident Preparedness And Resilience, Data Exfiltration Prevention